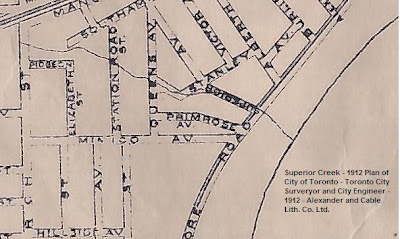

This map shows the lost creeks of south Etobicoke (present day City of Toronto) as they existed in 1811 superimposed over the street grid of today, courtesy of the Toronto and Region Conservation Authority. I first began the study of these creeks in 1996 when I researched and wrote Toward the Ecological Restoration of South Etobicoke.

This map shows the lost creeks of south Etobicoke (present day City of Toronto) as they existed in 1811 superimposed over the street grid of today, courtesy of the Toronto and Region Conservation Authority. I first began the study of these creeks in 1996 when I researched and wrote Toward the Ecological Restoration of South Etobicoke.At the time, I was the President of the Citizens Concerned About the Future Of The Etobicoke Waterfront (CCFEW), a not-for-profit group dedicated to the protection and restoration of the waterfront in south Etobicoke. The report documented the environmental history of the area, and proposed a number of restoration projects. Since that date many of the restoration projects have been accomplished in partnership with the Toronto & Region Conservation Authority and the City of Toronto, while some are still under consideration. Copies of the report are in the circulating collection of the Toronto Public Library.

I took up the research again in 2008 when I was asked to write a chapter on the lost creeks for HTO Toronto's Water from Lake Iroquois to Lost Rivers to Low-flow Toilets, published by Coach House Press in 2008. At the time of my original research I was only concerned with the area south of the Gardiner Expressway as it is a natural northern boundary for south Etobicoke. Remnants of these creeks still existed in certain locations in south Etobicoke. I had thought that all the post WWII development north of the Gardiner Expressway would have obliterated any trace of these historic creeks long ago. How wrong I was! I was surprised to discover that Jackson Creek still flows above ground for a considerable distance to the north.

This is the story of the lost creeks of south Etobicoke. The 1811 patent map that lists the original landowners in what is now south Etobicoke provides an excellent view of the creeks that existed at that time, including North, Jackson, Superior and Bonar Creeks. The lives of these watercourses were inextricably linked to the use of the land within their watersheds. Originally covered by thick forests, these watersheds evolved over thousands of years to become a finely tuned and balanced system that produced a steady flow of cool, clear and pristine water abounding in sensitive coldwater fish species such as salmon.

While most creeks and streams in the old City of Toronto were buried in sewer lines long ago, many of the original creeks and steams of south Etobicoke survived into the mid 20th century - and some significant portions still exist today! It took some considerable good luck and fortune that they lasted as long as they did. A considerable distance west of Simcoe’s new capital of York, the progression of south Etobicoke from forest to agricultural fields, and finally urban development was slower than areas closer to Toronto.

However you can still catch glimpses of many of these creeks and streams if you know where to look.

I can be contacted at lostcreeksofetobicoke at hotmail.com.

All information and photographs on this site are copyrighted and may not be used without my permission. No use for commercial purposes is permitted.

© Copyright Michael Harrison 2009. All rights reserved.